Transport Layer

The network layer provides end to end delivery of data, but machines typically have multiple applications running at the same time. How can I ensure that the email that I'm sending doesn't get picked up by the webserver application on the receiving end?

This is the job of the transport layer, to direct traffic to specific applications on devices.

There are two main protocols used on the Transport Layer, TCP and UDP.

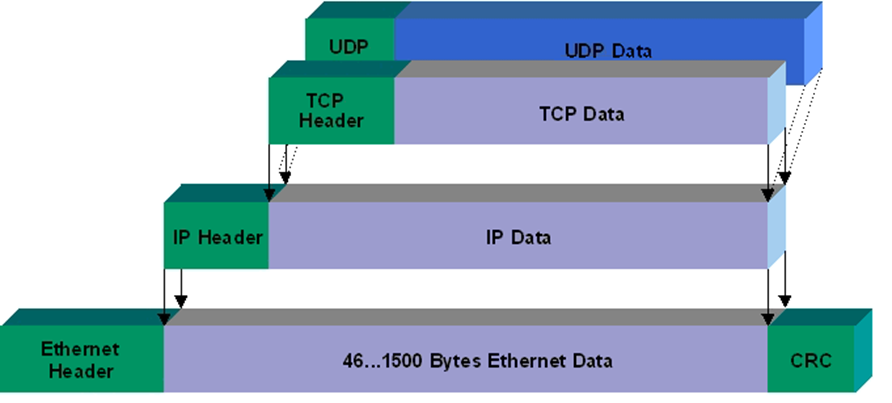

The Protocol Data Unit (PDU) for a TCP connection is called the segment, and for UDP it is the datagram.

UDP

We will start off with User Datagram Protocol (or UDP) as it is simpler.

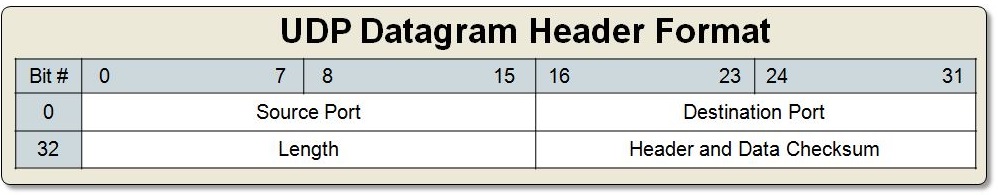

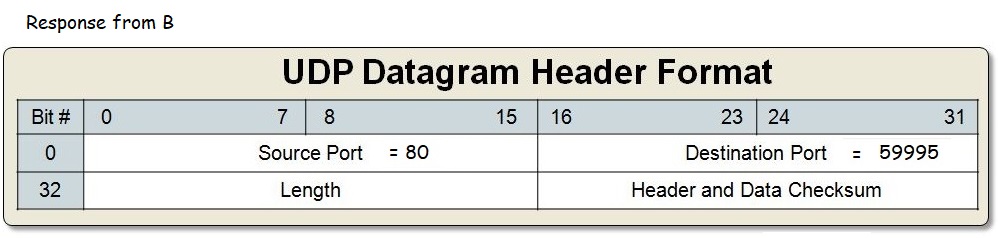

The header contains four fields: source port, destination port, length, and checksum.

Ports

The logical port (shortened to port) is used by both TCP and UDP. It reflects the address that a program can lease as long it's running.

There are 216 possible ports broken up into three categories:

- 0-1023: Well known ports

- 1024-49151: Registered Port

- 49152-65535: Ephemeral ports

Well known ports are reserved for system processes. You should avoid using these ports in your application unless your building a client or server for those protocols. On Unix accessing these ports requires superuser privileges.

Registered ports are more flexible, there are no specific restrictions with choosing to use a port in this range, you only need to be careful of what other major software also uses that port1. It is fine to overlap with other software, as long as you don't anticipate your users using that software at the exact same time as yours.

Finally we have Ephemeral ports, these are temporary ports automatically leased to applications by your operating system to be used for response type messages.

There's a wikipedia entry for common software and their port usage that I've linked to in the transcript appendix as reference.

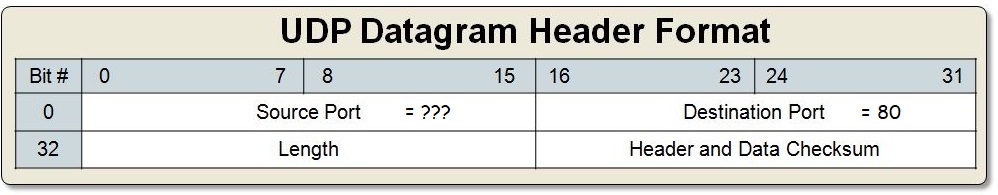

Imagine there are two machines A and B, both hosting a webserver on port 80 with different content. If A opens a web browser (different application) to visit B's website, That request whether it be TCP or UDP should have two port values, what are they? Destination port is easy, that will be 80. Your first guess might be port 80.

But if we use source port 80 there's a conflict with the webserver running on machine A. In fact using any fixed port will be problematic as it is increasingly common to visit two or more sites at the same time (watching YouTube while doing homework)

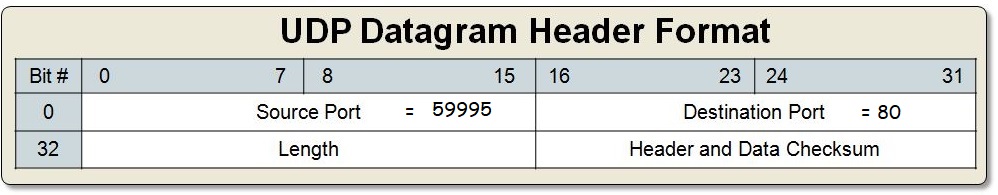

What actually happens is that when our client makes the request, the operating system will automatically lease it an available ephemeral port. This is set to be the source port.

When we gets a response back, the operating forwards the data to our application, then releases its hold to that ephemeral port. This allows our browser to make multiple requests to different servers and the timing in which I get my responses back no longer matters as they each have their own ephemeral port.

NAT (Network Address Translation)

Next we are going to take a detour back to the network layer, because something didn't make sense previously (if you noticed congrats!), that I couldn't explain it without knowledge of ports.

I mentioned earlier that when you purchase Internet service for your home you are leasing a single IP address. But how would that work if my home has multiple devices? If the single external IP address is shared between multiple machines how does my router know what device to route traffic to?

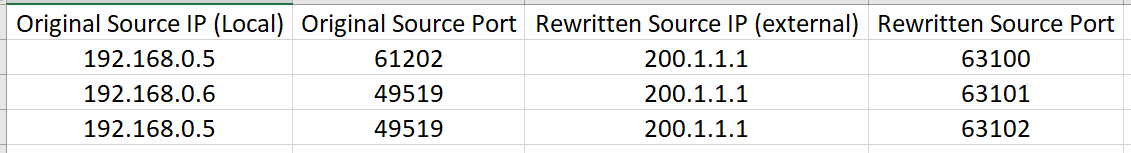

It uses Network Address Translation (or NAT) to do this. NAT is a technique that combines reserved local IP address space (192.168.0.0/16 range) and overloading ports to allow a single IP address to be shared among multiple devices.

Let's consider an example where two devices A and B, both on a home network (sharing a single external IP 200.1.1.1) are visiting the same website at 208.65.153.238. Both machines are assigned a local IP address by the router: A (192.168.0.5) and B (192.168.0.6).

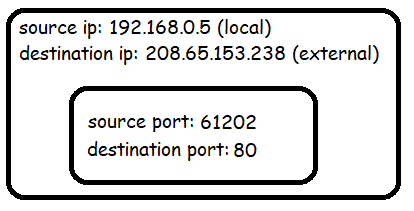

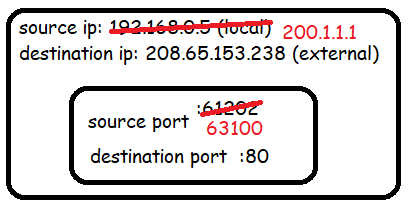

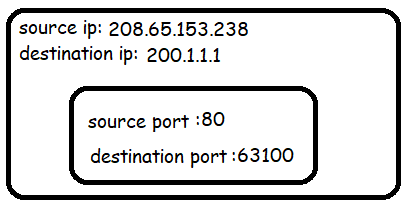

Consider a single packet from A to the website:

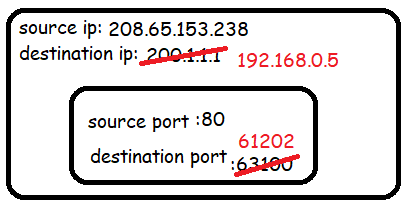

The router will see that the IP address 192.168.0.5 is owned by machine A. It will then rewrite the contents of the packet using the leased IP address and a new port number in the ephemeral range.

But it will keep all original values stored in a NAT table.

As the router is in charge of rewriting port numbers for all devices on the network, it can guarantee unique ports be assigned.

As the responses come back:

the router undoes this rewriting process using a lookup from the NAT table, this time on the destination IP and port.

Exercise: Trace what occurs when B sends a packet to the same IP address

208.65.153.238, show to yourself that multiple devices can share a single IP address thanks to NAT.

This is also why if you get your IP banned from some website, it's effectively banned for your entire household (at least until you lease a new IP address from your ISP by turning your router off for a few hours)

Port Forwarding

NAT works fine for most applications, but requires that your machine makes the first request.

What if you want to accept incoming connections without first sending out a request? For instance if you are running a mail or web server or a BitTorrent2 client.

In that case you need to do a bit of additional configuration from within your router. To setup port forwarding, you need to reserve a port on your router and tie it to a specific computer (and can optionally change the port). (Eg. all incoming traffic on port 443 should be forwarded to the IP address 192.168.0.5 (in the example above the port is rewritten to 440 too))

Socket

A socket is an instantiation of a port number that can communicate with the outside world. When a port is opened, a socket has been created. A port number is only an address, to be able to send/receive data, our application must explicitly tell the Operating System it wants to open a socket on that port number. This is also for security reasons.

We can open a socket on port 12345 in order to allow network communication to our application.

Transmission Control Protocol (TCP)

We will come back to UDP later, but let's introduce TCP.

Transmission Control Protocol (or TCP) provides reliable, ordered, and error-checked delivery of a stream of bytes between applications running on hosts communicating via an IP network. The PDU of a TCP connection is called a Segment.

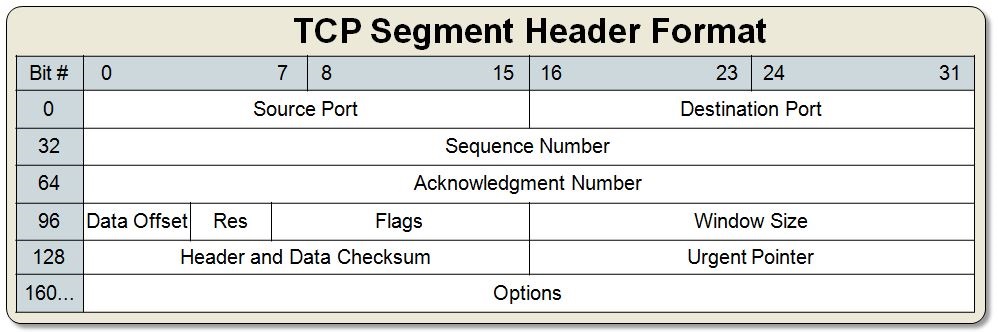

In order to make all those guarantees, the tradeoff we pay is a much larger header size. The most common TCP header size is 20 bytes (first 5 rows in the table above)

There is also quite a bit of overhead used for sending a receiving messages, as each segment of data must be acknowledged. Requiring another 20 byte header from the receiving end.

Structure of TCP Header

- Destination Port: Port that the traffic is intended for

- Source Port: Port that the reply should be directed to.

- Sequence Number and Acknowledgement Number: Used together to guarantee delivery of data.

- Data Offset: Indicates where the data begins.

- Res: Reserved

- Flags: Indicates the type of TCP Segment (See Flags)

- Window Size: Used for congestion control, tells sender how much data (in bytes) this device can receive at one point in time.

- Checksum: Provides Data Integrity. Personally I don't think data integrity is necessary since the data link layer also takes care of it, but there are counter arguments on the web 3

- Urgent Pointer (not important for us) : Intended to allow segment priority. (obsolete)

- Options (not important for us): Holds optional fields like maximum segment size, window scaling, selective acknowledgements, and timestamps

Flags

- ACK - Acknowledgement - The Acknowledgement Number should be inspected.

- PSH - Push currently buffered data to the application on the receiving end as soon as possible.

- RST - Reset - One of the sides of the TCP connection hasn't been able to recover from a series of missing or malformed segments and to restart the connection.

- SYN - Synchronize - Used when establishing a TCP connection and tells the receiving end to inspect the sequence number for synchronization purposes.

- FIN - Finish - Signals that one side of a TCP connection wants to terminate the connection.

- URG - Urgent: Segment has priority, the urgent pointer should be inspected (obsolete)

- Reference: ECE + CWR: Used in newer congestion control systems for switches.4

TCP Connection

There are four primary types of segments:

- A synchronization segment used when first establishing a connection [SYN]. (Only used in opening a new connection)

- A data segment used to encode a chunk of data (no special flag),

- An acknowledgement used to indicate data was received [ACK]

- A finish segment used to indicate a request to terminate a connection [FIN]. (Only used in closing a new connection)

Sender Perspective

Three way handshake

- One device (either sender/receiver) initiates a synchronization request [SYN]

- The other device sends back a [SYN+ACK] back

- The original device [ACK] the receiver.

-------------------- CONNECTION ESTABLISHED --------------------

The sender can then send data up to the receivers window size (window size is received in step 1.2) typically in segments of up to 65k bytes.

Each segment includes a sequence number representing the order of bytes sent relative to all other messages.

Wait for [ACK] segments

- As you receive [ACK] segments, begin sending data starting from the largest Acknowledgment number received. (send data up to the window size to ensure receiver is not overwhelmed with data, an updated window size will be included with their ACK)

- If you receive an acknowledgement with the same acknowledgment number two or more times. (Some data was likely loss) resend segments starting from the largest Acknowledgment number after waiting one round trip time (RTT) to collect additional duplicate ACKs.

- If the sender does not get a response within the Request Time Out (or RTO) time frame, it resend every segment starting from the largest acknowledgement number.

-------------------- DATA TRANSFER COMPLETE --------------------

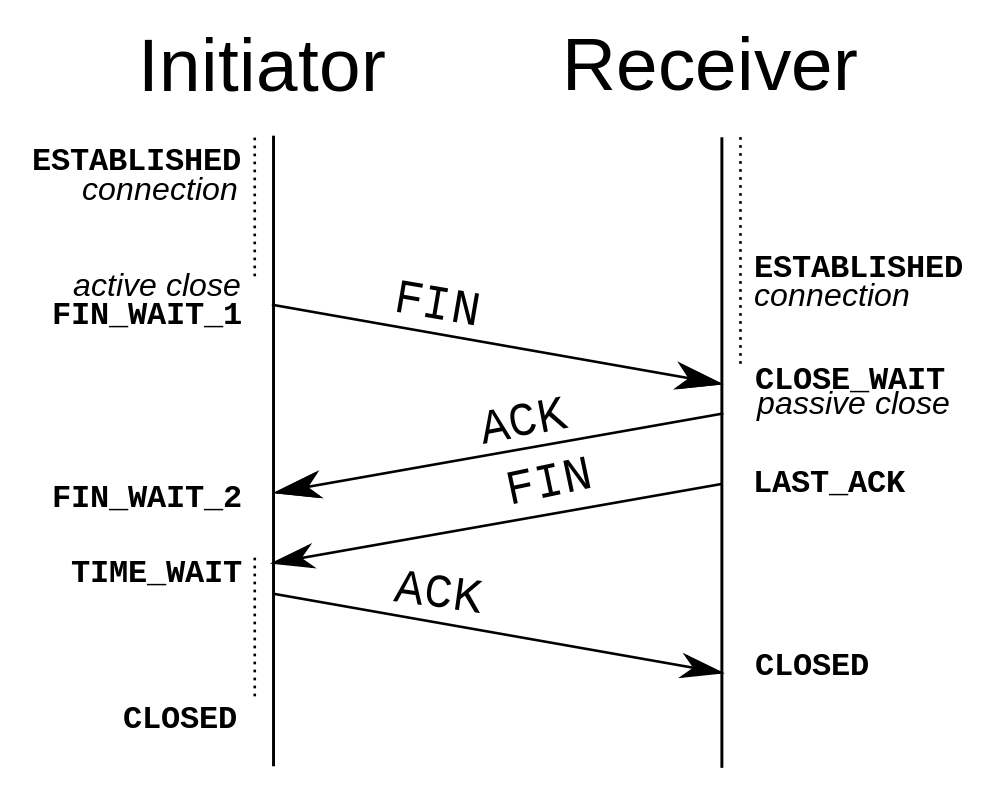

Four way closing handshake

- One device (either sender/receiver) initiates a [FIN] request to terminate the connection. (Just like starting a connection, either side can request to terminate it)

- The other device sends back a [ACK] back. Indicating the close request was received, and begins the process of releasing resources, before terminating the connection. (This may take time if we need to close a database connection or perform garbage collection)

- Once the local shutdown of the socket is nearly complete, a [FIN] is sent to the other side

- An [ACK] for that last FIN is sent and upon receiving it, the socket is closed and the port number is returned to the OS.

Receiver Perspective

Three way handshake

-------------------- CONNECTION ESTABLISHED --------------------

Waits for Data Segments containing sequence numbers.

For each segment received in the correct order, responses back with [ACK] segment containing: Acknowledgement number = Received Sequence Number + data.length This sent acknowledgement number indicates the next expected sequence number.

If a segment is received with a sequence number larger than the current acknowledgement number, a segment is likely to have been loss. Store the new out of order segment in memory and send an [ACK] with acknowledgement number set to be the missing segments expected sequence number. This will signal to the sender to resend starting from this segment.

Storing the previous segment allows the receiver to jump back to the later Acknowledgement number once the missing packet has been filled in.

-------------------- DATA TRANSFER COMPLETE --------------------

Four way closing handshake

TCP is duplex

We can send and receive at the same time, there are two sets of Sequence and Acknowledgement numbers, one on each side of the connection.

TCP Congestion Control

The receiver can tell the sender to speed up / slow down the transmission rate by adjusting the window size. This adjusts how many packets the sender can send without waiting for an acknowledgement.

Since this value can't go above 65535 bytes due to the size of the header, for modern applications there is a TCP option called TCP window scale that wo rks as a multiplier for this value allowing connection speeds of up to 1 Gigabyte.

UDP

Because every segment needs to be acknowledged TCP has quite a bit of overhead.

Silly Window Syndrome: Small payload with big headers

Applications that do not require a 100% reliable data stream may use the User Datagram Protocol (UDP) instead. UDP provides a connectionless datagram service that emphasizes reduced latency over reliability.

There are no guarantees of any kind, but there is also no need for acknowledgement segments. If data is loss or corrupted there is no built in way to recover the lost data.

It is up to the layer above it to perform any error recovery necessary to keep the application from failing entirely.

It is useful in situations where some data loss is okay:

- Video streaming: Artifacting of video

- VOIP: Distortion of voice

- Online multiplayer games: The programming of which is commonly referred to as netcode or lag compensation. It is the reason when playing multiplayer online games, a character may seem to teleport a bit when someone experiences lag. Instead of disconnecting the player on data loss, the game server can sometimes make some assumptions based on the players current direction and velocity and other previous input and will correct it once they come back online.

QUIC (Reference)

Modern transport layers like QUIC5 categorize their packets as UDP and build on top of it the reliability and congestion management features that TCP has, as most older routers only recognize TCP and UDP packets.

The benefit to this approach is to be able to pick and choose which features (and associated overhead costs) your transport layer protocol requires instead of choosing an out of the box solution that has everything.